Introduction

/For Sandy, among the stars

--------------------------------------

Burroughs’ career is counted out in transformations. There is no one Burroughs. – Victor Bockris

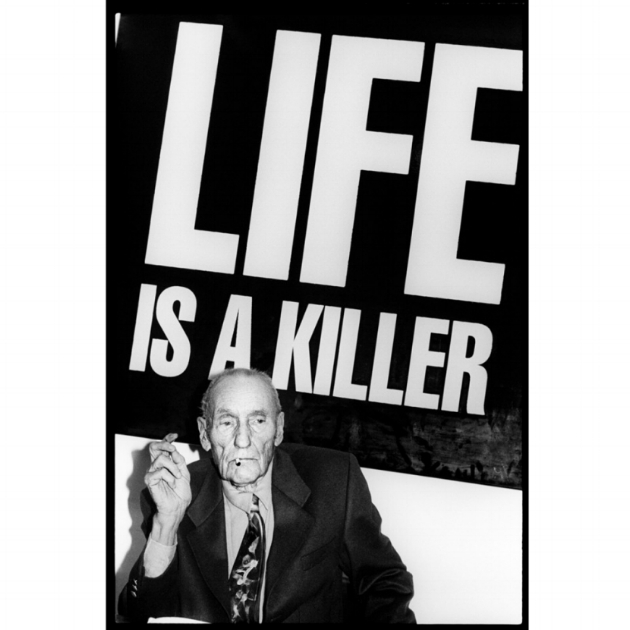

In 1995, towards the end of his life, William S. Burroughs posed for a picture by Kate Simon, who had worked with him over a period of 20 years. The octogenarian author is seen smoking a joint beneath a large black-and-white screen with big block text that screams LIFE IS A KILLER. Burroughs’ celebrity—or notoriety—was primarily earned as the writer of such groundbreaking novels as Junkie, Naked Lunch, The Wild Boys, and Cities of the Red Night, along with countless articles, essays, and interviews. He also turned heads in the fine arts world with his infamous “shotgun paintings”—which he made by blasting both barrels at a can of spray paint positioned near a plywood canvas affixed with collage. At age 81, Burroughs was a living icon who had inspired countless younger artists—especially musicians—over four decades of creative, psychological, and pharmacological exploration.

The most transgressive of the Beat writers, Burroughs was also something of a clandestine agent in the development of rock ’n’ roll—a spectral figure who haunted the cultural underground and helped usher it into the mainstream. His direct impact on musical artists over a half-century is immense but largely unexplored. From The Beatles, to punk, to today’s remix scene, Burroughs helped accelerate an evolution in sound that continues to reverberate across continents and eras. This book tells the story of his personal connection to musicians and how his influence continues to echo more than twenty years after his death.

Burroughs still had plenty of spark at his final photoshoot, holding pose for an extended period so Simon could properly frame him beneath a print made by his dear friend John Giorno. “I thought the screen was beautiful,” she remembered. “He was smoking a joint; this was the last shot I took of him. . . It’s something; life is a killer.” A potent statement, sharp and impossible to ignore, like a switchblade to the stomach. And true, to boot. “Born to Die” isn’t just the name of the second Lana Del Rey album—it is part of humanity’s source code, which according to Burroughs, was written onto our fleshy systems by an unseen and unperceivable operator that he called Control. “All species are doomed from conception like all individuals,” he said.

Burroughs spent his life researching and experimenting with ways to transform himself and the world around him. He did so through his writing as well as his work with audio—both of which inspired artists from Bob Dylan to Kurt Cobain, helping pave the way for today’s sample and remix-based music. It’s strange to think of this jazz age relic, whose gentlemanly manners belied an uncompromising intellect, having an impact on so many different genres. Still, there is little doubt that the music of the 20th century and beyond owes much to Burroughs’ methods and worldview.

Burroughs explored intense inner and outer landscapes and reported back his findings, typing up his reports with remarkable discipline, day in and day out. This commitment, in addition to his immense talent and intellect, makes him a rare creative visionary. But what did Burroughs see through his deeply scarred lens? Pure, insatiable need. Instead of running away, however, he examined it up close. Drugs, the occult, psychic home surgery—any and all of it was worth experiencing and documenting. Like the musicians he inspired, Burroughs was a fearless and intrepid reporter who not only cataloged his adventures, but used them as raw material to initiate real change in the world around him. In doing so, he opened up new creative vistas to others, who in turn reshaped culture using techniques that he helped pioneer.

Today, Burroughs the icon captivates imaginations as much as Burroughs the author. He expended great effort to depersonalize his work using cut-ups—a technique whereby pre-existing text, film, or audio is sliced up and rearranged—yet his biography has become as legendary as even his most celebrated novels. Here was a homosexual drug addict, born in the Gilded Age, who killed his wife in a drunken game of William Tell and wrote infamous prose featuring orgasmic executions, shape-shifting aliens, and all manner of addicts, sadists, and creepy crawlies. But there exists a real person within the legend, a man who exhibited genuine kindness and hospitality to those who knew him, including many of the musicians in this book.

In many ways, Burroughs is a cipher, a puzzle to decode. Like a multi-faceted prism or mirror, Burroughs reflects different things to different people depending on their own interests or agendas. To some, Burroughs is a junkie priest offering hardboiled wisdom from the narcotic underground. To others, he is a dark magus whose occult philosophies paved the way for today’s DIY sorcerers. Still others—especially recording artists and songwriters—find inspiration in his creative methods, including cut-up text and tape splicing. That there are so many different ways to engage with Burroughs’ work and worldview is key to the perpetuation of his influence. It allows other artists to take his vision forward, often in mutated form. Over time, this gravelly voiced son of Midwestern privilege has become like a space-borne virus from one of his books, hopping from host to host, medium to medium, each strain transforming culture in profound, though sometimes obscure, ways. This is just how he would have wanted it.

Burroughs is a highly significant figure in the world of music, even if he professed little knowledge about the form. It’s not hard to see how his writing—exploding with disquieting, even ghastly, imagery—might serve as fodder for music genres like punk, heavy metal, and industrial. To be sure, it is within these subcultures that the majority of present-day Burroughs acolytes are found. But his anti-establishment attitude and unconventional personal habits also found favor with such artists as Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, Lou Reed, Frank Zappa, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Laurie Anderson, and countless other musical innovators. The Beatles even put him on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band alongside the likes of Carl Jung, Lenny Bruce, Karl Marx, and Oscar Wilde. Once you start looking, Burroughs is everywhere.

His influence extends beyond the work itself to the actual methods used to create it. Burroughs’ focus on recombinant media—that is, cut-up text, “found sound” and tape splicing—would become the lingua franca of experimental audio production in the 1990s right up to today. He first began working with cut-ups alongside painter Brion Gysin in 1950s Paris. The original method involved slicing up pre-written text from one or more sources into quadrants and rearranging the pieces at random. Later experiments involved machine-based cut-ups devised by Burroughs’ lover Ian Sommerville, an early computer programmer. Going forward, Burroughs would embrace random elements in almost all of his work, especially his audio experiments, some of which were conducted on tape recorders provided by Paul McCartney in a flat owned by Ringo Starr. These experiments inspired the Beatles to include found sound and tape cut-ups on seminal recordings like Sgt. Pepper and The White Album, ushering in a new dawn for recorded sound.

It’s hard to imagine sample and remix-based music without Burroughs, or at least without the artists he inspired—David Bowie, Throbbing Gristle, and Coil among them. Hip-hop and electronic acts like Michael Franti, DJ Spooky, and Justin Warfield embrace Burroughsian ideas in their work, and a few were lucky enough to have collaborated with him. Arena-conquerors U2 used video cut-ups on massive global tours and sought Burroughs out for their 1997 video for “The Last Night on Earth”—his last filmed appearance. Countless bands got their monikers from Burroughs novels or incorporated phrases in song titles or lyrics. Steppenwolf, who are credited with bringing the term “heavy metal” to music, borrowed the phrase from Burroughs. Then there’s Steely Dan, who famously took their name from a state-of-the-art dildo in Naked Lunch. And there are others, such as The Soft Machine, Nova Mob, Wild Boys, and The Mugwumps, to name but a few. Iggy Pop and Patti Smith lifted lines directly from Burroughs and weren’t shy about letting the world know. At one point, synth-poppers Duran Duran attempted to make a full-length film based on their video for “Wild Boys,” a song that took its inspiration from a Burroughs novel of the same name. It’s like a game of “Where’s Waldo” set to a killer soundtrack. But instead of a chipper youth in a striped sweater, we’re looking for a wan junkie in an old fedora.

Burroughs was an intrepid investigator of the paranormal and maintained an active interest in what we would today call fringe science. He held sway over occult-minded artists like Genesis P-Orridge of Throbbing Gristle, Chris Stein of Blondie, and John Balance and Peter Christopherson of Coil. Jimmy Page, lead guitarist and magus-in-chief of Led Zeppelin, spent time with Burroughs discussing music’s supernatural potential and the connection between Zeppelin’s thunder and the Master Musicians of Joujouka—a tribe of Moroccan musicians Burroughs referred to as “a 4,000 year-old rock ‘n’ roll band.” Although he professed little firsthand knowledge of musical composition, Burroughs understood how performance could be used to affect reality. He delighted in Patti Smith’s shamanic stagecraft and the two became good friends. “He’s up there with the Pope,” Smith said of Burroughs. Bob Dylan practically chased him down for a meeting that took place at a Greenwich Village café in early 1965. Not long after, the po-faced folkie would re-emerge at the Newport Folk Festival as a wild-eyed visionary backed by a raucously heretical electric band.

David Bowie used cut-ups in his work from the 1974 album Diamond Dogs to Blackstar, released days before his death in 2016. Bowie called cut-ups “a form of Western Tarot,” and throughout his career credited Burroughs with helping to advance his own art and aesthetic. Erstwhile Bowie-associate Lou Reed was a Burroughs obsessive going back to his days with the Velvet Underground. Reed didn’t go in for cut-ups, but he did borrow a great deal from earlier Burroughs books like Junkie, with its matter-of-fact portrayal of the ravages of addiction and sardonic observations of street life. Both Bowie and Reed spent time with Burroughs in the 1970s—such scenes are recounted here, along with analysis of the recordings influenced by the author.

Burroughs spent much of his time abroad, living in Mexico, Morocco, Paris, and London, and making frequent trips back to New York City, where he moved in the mid-1970s. After a couple of downtown apartments, he settled into in a windowless former YMCA locker room affectionately known as “The Bunker.” The hideout sat just a couple of streets over from the legendary club CBGB in the seedy Bowery neighborhood. Here, Burroughs played host to the denizens of the emerging punk scene, including Patti Smith, Chris Stein and Debbie Harry of Blondie, Joe Strummer of The Clash, and Richard Hell of the Voidoids, to name but a few. Though Burroughs more or less rejected the “Godfather of Punk” title bestowed on him affectionately by the press, he did find the new generation to be more interesting than the hippies. He even sent the Sex Pistols a letter of support when they took heat for “God Save the Queen,” their monarchy-bashing single from 1977. “I’ve always said that England doesn’t stand a chance until you have 20,000 people saying ‘Bugger the Queen!’” Burroughs enthused.

In 1978, a coterie of musicians, writers, and performance artists came together to celebrate Burroughs’ return to the U.S. at the Nova Convention, held at the Entermedia Theater in New York. Frank Zappa read one of the more notorious bits from Naked Lunch, the “Talking Asshole” routine; Smith, suffering from pneumonia, nonetheless delivered a righteous reading backed by her loyal axeman Lenny Kaye; Laurie Anderson brought an experimental edge to the proceedings with pitch-shifted vocals and sparse electronics; Philip Glass melted minds with his then-new composition, “Einstein on the Beach.” The afterparty boasted performances by Suicide, Blondie, the B-52s and King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp.

Punk begat industrial music, including the groundbreaking sonic assaults of Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV—two bands led by “occulture” doyen Genesis P-Orridge. One would be hard-pressed to find a more persistent evangelist of the Burroughs worldview than P-Orridge, who has a great many stories and observations about the emerging industrial scene and Burroughs’ covert role in shaping it. P-Orridge is the link between Burroughs and the tech-enabled “chaos magicians” who began colonizing the weird wide web at the advent of dial-up. Burroughs did not live to see the internet become the force for creative, social, economic, cultural, and political disruption that it is today. But he would no doubt have recognized it for what it is: a cut-up. Today, we are positively bombarded with fragmentary sounds and images, recombined and often weaponized to serve one agenda or another. What do we call it when one of these “small units of information” holds brief sway over our consciousness? We say it “went viral.” Somewhere in space-time, the old man twists his thin lips into something resembling a smile.

Burroughs continued to impact the world of music after he moved to Lawrence, Kansas at the turn of the new decade. His early spoken word and tape splicing experiments were collected on Nothing Here Now but the Recordings, originally released on Throbbing Gristle’s label, Industrial Records in 1981. That same year saw a joint album featuring Burroughs, performance poet John Giorno, and experimental musician Laurie Anderson called You’re the Guy I Want to Share My Money With—Anderson’s first official release. Not long after, Burroughs appeared on records alongside artists like Nick Cave, Tom Waits, Butthole Surfers, Swans, and David Byrne. The 1990s saw Burroughs, then in his late 70s, become even more of a hero to the music world. He wrote the text for The Black Rider—a theatrical collaboration with Robert Wilson and Tom Waits, which was also released as a Waits solo record. On it, Burroughs can be heard singing the standard “'T' Ain't No Sin” in his creaky drawl. A “magical fable” that borrows from Faust and echoes Burroughs’ accidental shooting of his wife, The Black Rider is still performed around the world to critical acclaim. The spoken word album Dead City Radio appeared in 1990, and included background music by Donald Fagen of Steely Dan, Sonic Youth, and John Cale. Once again, it contains Burroughs’ singing, this time on a charming version of the Marlene Dietrich warhorse “Falling in Love Again.”

In the ’90s, Burroughs didn’t travel much anymore, but plenty of notables came to him. The final decade of his life saw him hosting the likes of Kurt Cobain, Sonic Youth, and members of R.E.M. and Ministry at his red bungalow in Lawrence. In 1992, bassist and producer Bill Laswell released The Western Lands, based on Burroughs’ book of the same name. That same year, Ministry sampled Burroughs in the song “Just One Fix”; he also appeared in the video. Burroughs collaborated with The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy for Spare Ass Annie and Other Tales, released in 1993. Burroughs and Cobain released a record together, The Priest They Called Him, shortly before the latter’s suicide in 1994. In 1996, Burroughs teamed up with R.E.M. for a cover of their song “Star Me Kitten,” and time-traveled back to the 1960s for a bizarre mashup with The Doors, “Is Everybody In.”

Today, Burroughs’ sway over the music scene is somewhat less pronounced. And yet his influence is often the most persuasive when his presence is hardest to detect—they didn’t call him El Hombre Invisible for nothing. Music is actually just the tip of the iceberg. Burroughs’ impact on a range of popular media—including films, comics, video games and other literature—is equally immense. He predicted a future where minds would be literally infected by “very small units of sound and image” distributed en masse and electronically, which we see in today’s meme wars on social media and at certain message boards like 4Chan, where hordes of young, mostly male, raconteurs engage in ceaseless rage-attacks against tolerance and reason. “Storm the citadels of the Enlightenment,” Burroughs once wrote. It is rapidly becoming a truism that on the internet, “nothing is true; everything is permitted,” to borrow one of his favorite turns of phrase. The stories captured in these pages demonstrate that Burroughs not only foresaw, but may even have helped initiate, our increasingly chaotic present and uncertain future. Still, the most enthusiastic ambassadors of his worldview happen to be musicians. Those appearing in this book serve as a Rosetta Stone for understanding key aspects of Burroughs’ work, which predicted so much about our current society and may have more to reveal about where we are going.

This book is about music, musicians, and William S. Burroughs. It is also an account of the social, political, and technological transformations that have transpired since Burroughs committed to “writing his way out” of his own personal traumas—many of which were self-inflicted. The musicians who gravitate to Burroughs have a lot in common with one another, even if they come from highly divergent backgrounds. All of them burn with a desire to break out of the ordinary, to escape social or institutional conditioning. No doubt some of them just wanted to hang out with the Pope of Dope, but his most intrepid devotees made waves using the author’s techniques and aims. Their adventures are recounted here, interwoven with Burroughs’ own biography. In this way, a broad range of concepts, ideas, methods, obsessions, and outcomes are explored, connecting everything from EDM to hip-hop to punk to heavy metal to drug culture to the occult to media to technological dystopia.

As the author of this book, I can tell you plainly that even I had no idea when I began writing just how many fascinating—and deadly relevant—intersections are found in the Burroughsverse. But remember, this is just one facet of the mirror—a collection of impressions from the world of music, which in turn informs and shapes the broader culture. The real-world interactions between Burroughs and musicians described in this book are hilarious, head-scratching, and life-altering, just like the best of his writing. Burroughs said the only reason to write is “to make it happen.” The artists within these pages all changed society in ways large and small. Like Burroughs, they are world-travelers, experimenters, addicts, chameleons, influencers, and soothsayers. Like Burroughs, their bold excursions on the fringes of creativity—even sanity—serve to broaden our own horizons and inspire worthwhile expression across many media.

If this were just a collection of vignettes where Burroughs hangs out with rock stars, it would be plenty entertaining. But there is much more to the story. I see this book as a tribute to all great artists who push the limits, even when their efforts come at considerable cost. And everything has a cost, because everything is a hustle. Sex, drugs, religion, politics, finance, technology. . . we’re all marks in some pusher’s game. And they all aim to get us good and hooked. Of course, we’re always hungry to score—forever hunting for some small distraction from the pains of our own existence. It’s no fault of our own. According to Burroughs, our flesh is already infected with the prewritten script—we are the soft machines upon which the “algebra of need” is encoded.

**********

There are quite a few Burroughs biographies on the market, many of them worthwhile. One of the first, Ted Morgan’s Literary Outlaw: The Life and Times of William S. Burroughs, is based on interviews with the author and his associates. The more recent Call Me Burroughs: A Life, by Barry Miles, is a doorstop that doesn’t skimp on the details. Other books cover more esoteric ground, such as Scientologist! William S. Burroughs and the Weird Cult by David Willis, or The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs, by Matthew Levi Stevens. Victor Bockris deserves credit for capturing many fascinating conversations between Burroughs and the art stars of the 1970s in With William Burroughs: A Report from the Bunker. This book is not meant to replace those titles, but rather to supplement them with additional insights and analyses specific to the world of music. However, it is necessary to delve into Burroughs’ biography in order to establish the themes that connect to the musicians’ stories in this book. Our tale for the most part unfolds chronologically, though it occasionally skips around on the “time track,” to borrow a Burroughs phrase. The reason for this is because Burroughs’ personal history begins well before the advent of rock ‘n’ roll. Readers will encounter the bulk of his biography in the first couple of chapters, after which his life trajectory begins to line up with the music-centric material. If you’re already familiar with his life story, you will no doubt discover additional ideas to consider. And if you’re new to Burroughs, don’t be surprised if you’re hooked right out of the gate—his story is incredibly compelling.

I remember my first shot of William S. Burroughs. It was 1988, when I was a freshman in high school following around a pair of upperclassmen who were in a covers band that played the school dances. They were, and remain, cooler than that description warrants. And I’m not just saying that because they let a precocious motormouth follow them around. These kids were enthusiastic explorers of art and culture, from Dylan to Dada. They expanded my literary horizons and helped turn me into a half-decent guitarist and recording geek. Frankly, I was lucky. Hoping for any glimpse of a world beyond my no-horse New England town, and encouraged by my older peers, I consumed primo VHS fare like Repo Man (directed by Burroughs enthusiast Alex Cox), and listened to Sonic Youth back when they only played noise. Sandwiched between the Vonnegut and the Brautigan on my friend’s bookshelf was Naked Lunch, published thirty years earlier—an infinity to a sixteen year-old. Yet the words were like a live wire jacked straight into my still-developing cerebral cortex. I had been infected.

An early reader, I had already torn through the gothic literature at home, polishing off the likes of Bram Stoker, Edgar Allan Poe, H.G. Wells, and Jules Verne. Fervid peeks at the topmost shelf, where Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller were rightfully paired, offered a window into a more lascivious world. But nothing, not even H.P. Lovecraft—Burroughs’ cosmic horror doppelganger—could have prepared me for Naked Lunch, with its alternately horrifying and hilarious visions of drug abuse, carnality, and monsters both human and insectoid.

These days, kids can get their hands on all manner of subversive media at the flick of a fingertip. Back in the ’80s and decades prior, it took real effort. First off, things cost money. You couldn’t just download a song, movie, or God forbid, a book for free on the internet. It took a lot of mowed lawns and shoveled driveways to purchase even the relatively small number of Cure albums available at the time (I speak from experience). My interest in Burroughs was reinforced by other media, especially music. I remember hearing about Kurt Cobain’s audio collaboration with Burroughs, the 10” single The Priest They Called Him back in 1993, and driving a town over to the only decent record store to see if they had it. They didn’t, but I made damned sure that the record store I managed a handful of years later did. By the mid-1990s, I had read most, if not all, of Burroughs’ novels, and whatever nonfiction I could get my hands on. I recall being particularly taken by The Job, which grew out of a series of interviews conducted by Daniel Odier in the 1960s, when Burroughs was living in England. It was less of a Q&A than a stream-of-consciousness rant, in which Burroughs put forward the notion that language is literally a virus which infected the human larynx early in the development of our species. This virus caused a mutation in the biological animal, and in turn remapped our mental circuitry. Whether this idea had any basis in evolutionary theory was unimportant: it was wildly entertaining, as was the author’s syntax—spare, but with its own weird meter, sort of like Charlie Watts drumming in the Stones. Later on, when I heard one of his taped readings, it only amplified these qualities, clearing further space for this high strangeness to flower in my mind. As a creative person, Burroughs inspired in me a kind of fearlessness, an urge to experiment, and a sense that no matter how alienated I felt, I wasn’t alone. There were others like me.

Creative people need other creative people, as is clear from the stories in this book. Many young artists endure intense personal struggles, often related to feeling like outsiders of some kind. This is probably why small groups of artists form bonds—it’s a survival strategy, a kind of social insurance in an antagonistic world that tends not to tolerate free thinking. This is as true now as it was when Burroughs was a young man in New York in the 1940s, where he felt the pangs of romantic rejection, developed his unique approach to composing scenes, and got hopelessly hooked on heroin. As a member of what came to be known as the Beats, Burroughs, along with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and a motley cast of supporting players, upended American literature and seeded a counterculture that persists to this day. Not long after came rock ‘n’ roll, which boasts its own pantheon of renegades and outsiders. Even when their audiences number in the thousands or millions, rock stars tend to operate in small tribes. A band is a tribe. A substitute family. Because with a few exceptions, artists tend not to have great histories with their original ones.

Burroughs’ circle, relatively small but highly engaged, enabled him to float new ideas, and conduct experiments of the metaphysical and pharmacological kind. His friends helped him complete his masterwork, Naked Lunch—a product of “team editing” by Ginsberg, and Kerouac, who both looked up to him for many of the same reasons that the musicians did later. Burroughs might not have deliberately sought his status as the Godfather of Punk, but he is nonetheless the ultimate antihero, someone who refused to be conditioned by establishment norms. To be sure, some of his disciples may have been indulging a lifestyle crush, at least at first. But even that is interesting. What kind of person gravitates to a guy who shot his own wife? What kind of person admires an unrepentant addict? Who would want to hang out with a weird old junkie who lives in a windowless Bowery basement? As it turns out, quite a few. And I probably have all of their records.

As someone who carries the “Burroughs gene”—that is, has taken more than a passing interest in his life and work—I remain drawn to his fierce intellect and black humor, as well as his refusal to conform. But there’s more to it than vicarious thrill-seeking. The more one reads Burroughs, listens to his recordings, or examines his interviews, the further one is drawn in. Burroughs occupies his own universe; an area beyond known space-time coordinates where he serves as both sovereign and ambassador. To travel with Burroughs is to see the world you thought you knew get cut-up and reassembled in strange, funny, and sometimes frightening forms. Burroughs isn’t just the ticket, he’s the locomotive and the tracks; the rocket and the launchpad. Of course, you’ll never understand William S. Burroughs by reading about him. Just like you’ll never understand a record by looking at it. You have to sample the wares, kid. Good thing there’s plenty to go around: interviews, essays, videos, albums, and of course, books, to which I am honored to add my own. Now, go ahead and get yourself hooked.